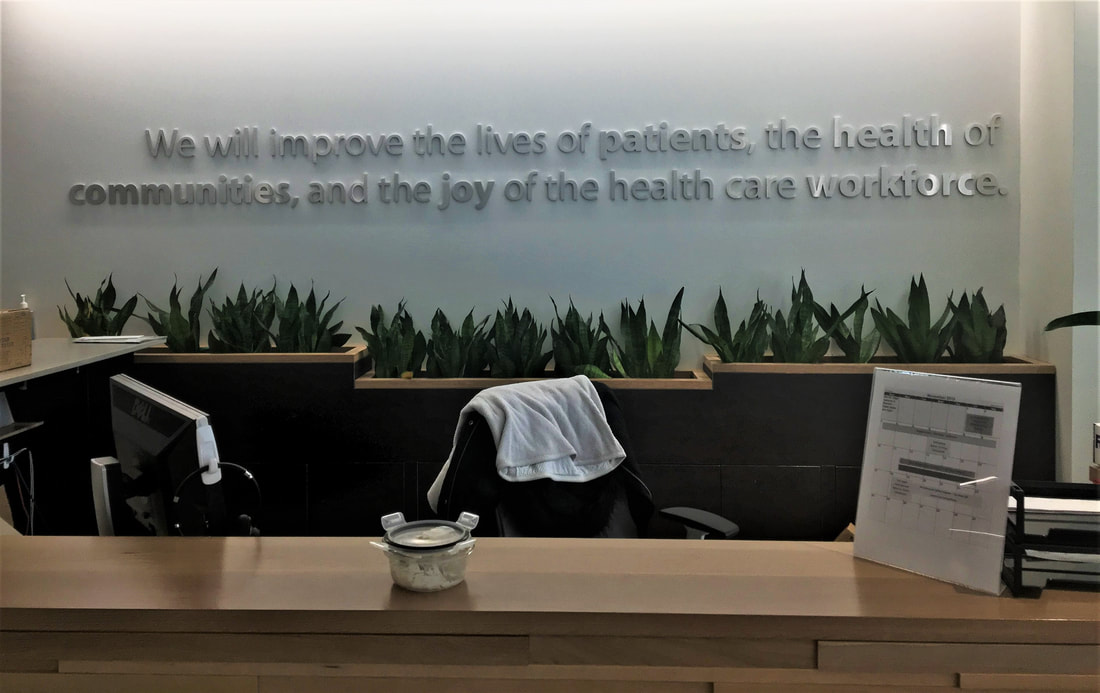

As long as I’ve known about evaluation, I’ve known about David Fetterman. Together with my colleague, Abe Wanderman, they developed the field of empowerment evaluation in the mid to late 1990s. However, David also draws from an anthropological background when he approaches research and evaluation. Recently, he published the 4th edition of his Ethnography text. Knowing nothing about this area of his work (nor having read previous editions), I dove in. David took the cover photo himself on his way to base camp!This isn’t a book review. I don’t have any referent point with which to judge the quality of the except that I know David generally does quality work Instead, I’d like to zero in on two methodological topics that stuck out: Unobtrusive Measures and the Analysis of Qualitative Data. This first article in a two-article series deals with the unobtrusive measures.  I’ve recently become fascinated with the idea of observational and artifactual data. These are measures that are independent of the respondent and should be somewhat objective whoever looks at them. There are many potential biases with self-reported measures. People can over or underestimate their ability, try to answer according to what the evaluator or researcher wants, etc. The Wandersman Center emphasizes the role of readiness in implementation efforts. Specifically, we are interested in building readiness: helping organizations and communities improve their momentum and capacity to implement an innovation. However, it is the case that most of the organizations that we work have a higher “floor” of readiness than what we would probably find in a random sample. There is self-selection going on whereby organizations that have enough readiness to seek our services, either through contracts or grant mechanisms, are going to be the ones who get funding. This also an issue for funders, who are likely to only make investments in resources and capital to organizations that have a likelihood of making progress. Readiness for support services becomes an equity issue. Organizations that have higher readiness are the ones with the opportunity to improve. And how are organizations selected for funding? Through grant applications or surveys whereby respondents try to demonstrate they have sufficient readiness to make progress. There are many organizations, either in strategic locations or with access to special populations that never get the opportunity to improve because they lack the readiness to reach out for resources. So, we’ve become interested in seeing whether there are other indicators of organizational readiness that are not dependent on a direct response from a person. Could there be observable behaviors or artifacts that might indicate whether an organization’s culture is receptive to a change? Some organizations post their mission statement or values around the office with the expectation that this will lead to a norming of these values, like with the picture below. There may be some tangible demonstrations of how leadership supports initiatives. The energy and dynamism of an office might be reflected in laughter, interactions, and openness. Courtesy of our friends at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Or not. We haven’t tested any of these measures yet. In the SCALE project, we tried to develop a list of measures that we could collect regularly that would remove the need for regular administration of the Readiness Diagnostic Scale. While we did come up with about 20 or so coalition-level processes that we might be able to monitor, we never were confident enough that move this into our regular evaluation plan. We instead relied on analyzing written products (like improvement plans and updates) for understanding coalition progress. We heard a rumor through the grapevine that RWJF had commissioned a study of coalition-level indicators of success, but the last time we heard an update of this work was in 2017. Further, community coalitions, while organizations themselves, are likely to have a much looser structure and therefore might not get at the organization-level factors we are looking for. We do believe, though, that being able to get a sense of an organization’s readiness outside of surveys might be a useful method in expanding the pool or organizations “eligible” for improvement. We know that readiness can be enhanced with targeted support; unobtrusive measures might be a way to describe organizational profiles so that training and tools might be provided at scale to a larger number of organizations. Rather than work with the organizations with time to respond to grants or surveys, we might be able to work with more. HOWEVER. From an Empowerment Evaluation perspective and from a Community Psychology perspective, it is important that participants be able to tell their own stories through their own data. If we try to remove the respondent from a readiness assessment process, we take away their autonomy in this regard. Further, there can be something very patronizing about parachuting in and saying, “You need to improve and this is how we do it.” There is also the basic ethical concern that we are gathering and using data without permission, even if said data is publicly available. So, this is kind of a catch-22. We want to empower people by removing barriers to evaluation, but we also don’t want to take evaluation out of their hands. I haven’t found a solution to this dilemma. Using a mixed-method approach kind of work, but the problems are only lessened, not removed. We welcome other thoughts about this…

1 Comment

12/1/2019 10:47:25 pm

DF: Jonathan – thanks for your thoughtful post and reference to my latest edition of Ethnography: Step by Step. My family and I just returned from Vancouver where I received the American Anthropological Association’s Presidential Award in large part for my new book and for “excellence and innovation in applying anthropological insights to the evaluation and improvement of education, social, and health services”.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed