|

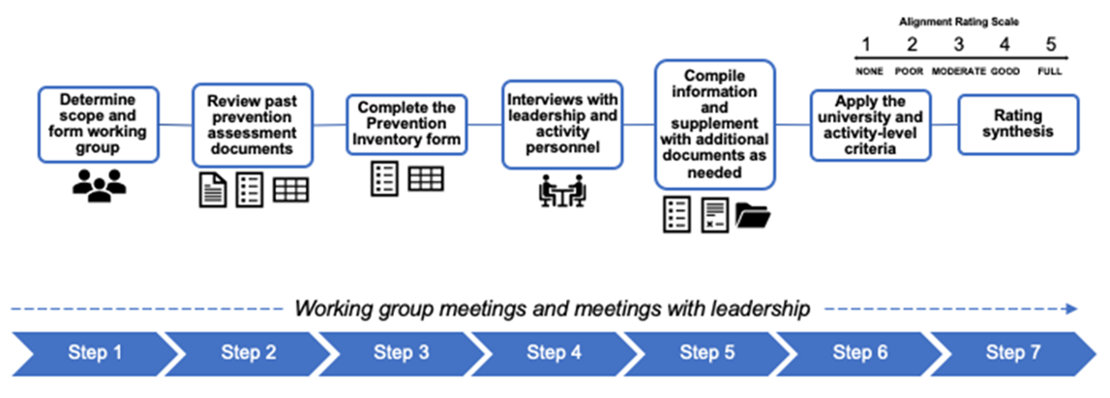

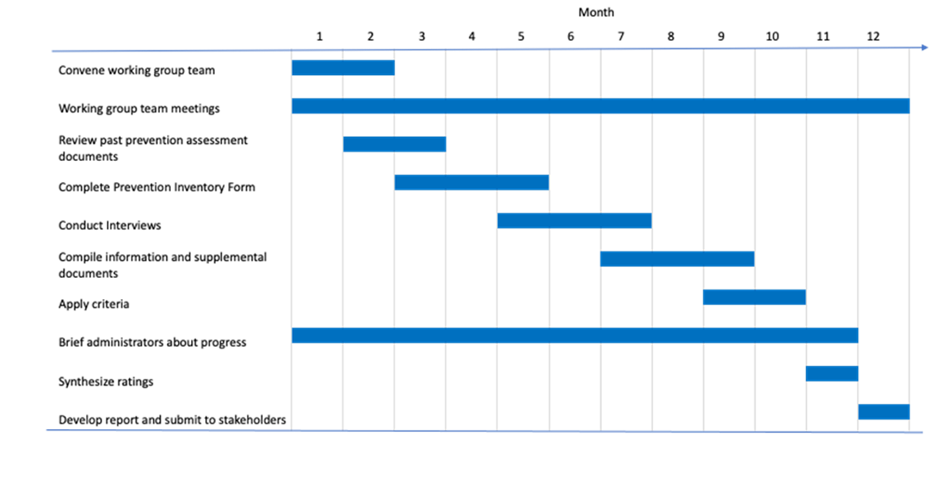

Sexual assault is a serious problem on college and university campuses. A new step-by-step guide can help university leadership understand how their efforts align with best practices in prevention and what support must be provided to prevention staff to ensure high-quality implementation. Colleges and universities in the United States have the responsibility for ensuring the on-campus safety of almost 20 million students. One area of student safety and wellness that has received increased attention in recent years has been campus-based sexual assault prevention. While the federal government and researchers have both been pursuing new strategies for prevention and response to sexual assault and harassment, evidence suggests that these efforts have not yet been successful. As many as 25% of college students have reported being sexually assaulted or harassed – a large number given the range of negative impacts sexual assault and harassment can have on survivors (including an increased risk of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse). Click the "Read More" button below to read the rest of the blog post. Prevention’s Lack of Success Institutions of higher learning have never been particularly adept at preventing sexual violence. Both policy experts and advocates for survivors say that schools have a history of not fully supporting prevention or response efforts related to sexual assault and harassment. This could be in part due to colleges and universities not being fully held accountable for Title IX violations. This began to change during the Obama administration, during which over 300 institutions were put under investigation for such violations. During 2011-2014, the federal government provided detailed guidance on how schools should better prevent and respond to sexual violence. Despite this guidance, many current approaches to campus-based sexual assault and harassment prevention leave something to be desired. The vast majority of such programs do not show evidence of reducing rates of sexual assault. The most frequently implemented programs on college campuses, such as bystander trainings and online training modules, have been shown to increase students’ knowledge of sexual assault and related topics (such as how to define consent) and improve students’ prosocial attitudes. These programs also improve students’ active bystander skills, but to a lesser extent. The hope is that students will use these newfound skills to intervene in dangerous situations that might precede sexual assault and prevent a potential assault from happening. While colleges and universities have hoped that increasing student knowledge and skills and improving student attitudes can lower rates of sexual assault, this has not proven to be the case. On the contrary, programs that demonstrate evidence of improving knowledge and attitudes have not yet demonstrated effectiveness in lowering rates of victimization or perpetration of sexual assault. “What Right Looks Like” For these reasons, it has been difficult to nail down “what right looks like” when it comes to campus-based sexual assault prevention programs. However, we do know what right looks like when it comes to broader aspects of organizational functioning that contribute to the likelihood of success for interventions and prevention initiatives more generally. Using these principles, we have worked with the Wandersman Center, the RAND Corporation, and the Department of Defense’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO) to determine how these general best practices can be used to guide evaluation and improvement of sexual assault prevention at both military service academies (MSAs) and civilian colleges and universities. Improving sexual assault and harassment prevention first requires evaluating and improving the capacity of organizations implementing prevention programming (e.g., MSAs and civilian colleges and universities). Organizational functioning, or capacity, refers to an organization’s ability to function effectively and productively on a daily basis and to implement the work necessary to reach the organization’s stated goals. During the early stages of this work, we cross-examined several frameworks dedicated to guiding the implementation of evidence-based prevention initiatives to identify several areas of organizational functioning or capacity important for sexual assault prevention. The frameworks reviewed included the Department of Defense’s Prevention Plan of Action, the Getting to Outcomes model, the R=MC2 Organizational Readiness model, and the CDC’s Five Pillars for Comprehensive Sexual Assault Prevention. Components of organizational capacity highlighted by these frameworks included the importance of leadership support, workforce support, collaborative relationships, proper data collection and evaluation procedures, and sufficient resources. We then translated these organizational components into a set of criteria that could be used to assess how closely an organization aligns with these best practices. An additional set of criteria was created to evaluate individual prevention activities based on the principles of effective prevention. These two sets of criteria were the basis for a manual first developed to guide MSAs in assessing their own sexual assault and harassment prevention efforts (the manual was first devised for military sites given the already-established relationship between the Wandersman Center and SAPRO). This manual was pilot tested at several MSAs. A parallel version, designed to be more appropriate for civilian colleges and institutions, was then created. This translation was reviewed by prevention staff at several universities across the country who provided comments for how to improve the manual, which led to revisions and improvements to increase adoption, offer additional information and support for users, and provide guidance for adapting the manual to fit specific contexts. University Self-Assessment Guide The resulting product is a step-by-step instruction manual providing university prevention staff and leadership with guidance on how to assess their institution’s adherence to 65 criteria that represent best practices in prevention at both the organizational and activity levels. This manual walks users through how to form an interdisciplinary working group, facilitate group functioning, gather data on prevention efforts, apply the criteria, and ultimately generate recommendations for improvement. A graphic from the guide detailing the seven steps in the self-assessment process can be seen below, as well as an illustration of the approximate timeline for completing the self-assessment. While the university manual has yet to be piloted, it is intended to increase university stakeholders’ knowledge of best practices in prevention programming and empower them to assess how closely their efforts toward sexual assault and harassment prevention align with these practices. These efforts to improve institutional knowledge, evaluation, and action may be our best hope at reducing rates of sexual assault and harassment.

The University Self-Study Guide will be available for free download on the RAND website soon. We will provide a new blog when it comes out, which will include a link to access the guide.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed